Part of instituto de visión’s { ᴠɪsɪᴏɴᴀʀɪᴏs } program, Calentamientos presents works by Miguel Ángel Cárdenas (1934), a Colombian artist and pioneer in electronic media, performance and installation. Cárdenas’ practice raised bold issues for the sixties, such as sexuality, eroticism, moral paradigms and Colombian cultural models versus their European equivalents.

In this exhibition a selection of works are presented that deal with the concept of human warmth as understood in terms of its most naïve and innocent of connotations (the idea of been able to transform a rationalist and cold culture, such as that of the Dutch, with a tropical temperament), as well as in terms of its most perverted of sexual connotations. Cárdenas, who confirmed his homosexuality when he arrived to Europe in 1962, always tried to escape moralist postures such as those that existed in Colombia at the time.

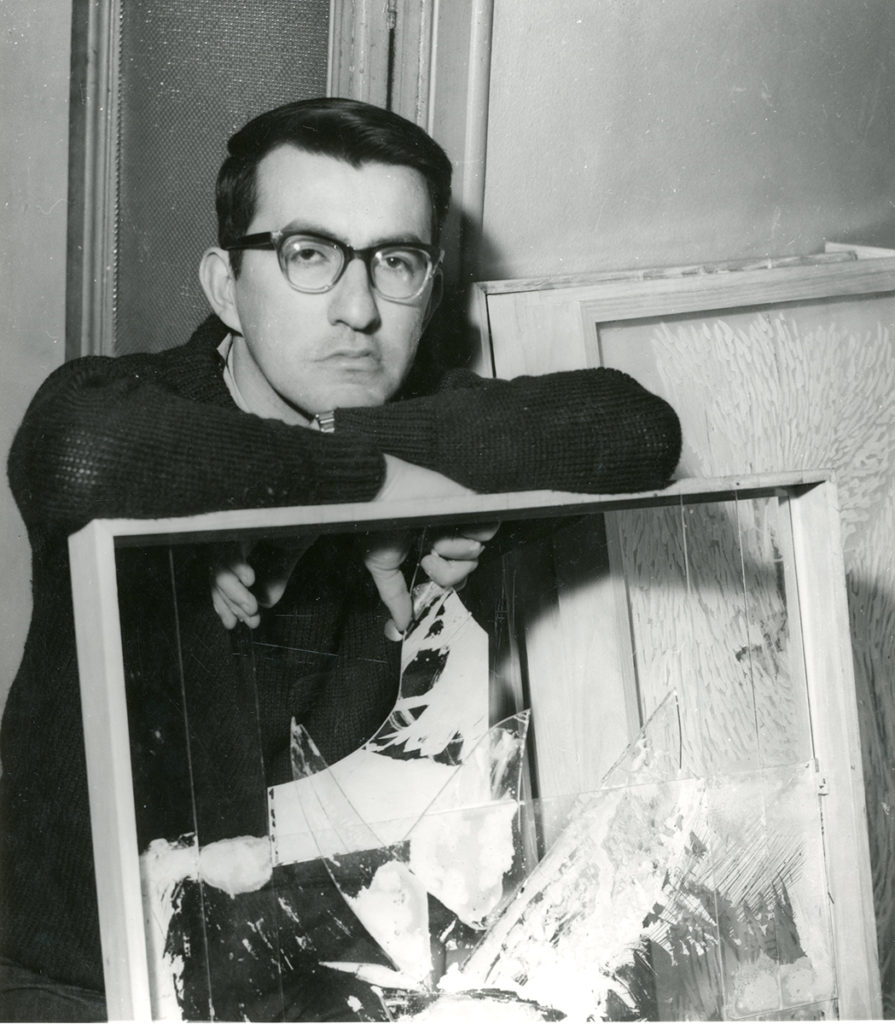

With his early abstract paintings, Miguel Ángel Cárdenas entered institutional collections and achieved recognition in the local art scene. Yet his creativity was contained. Reading Jean Genet opened up others realities and mores, stimulating him to create performances and video art.

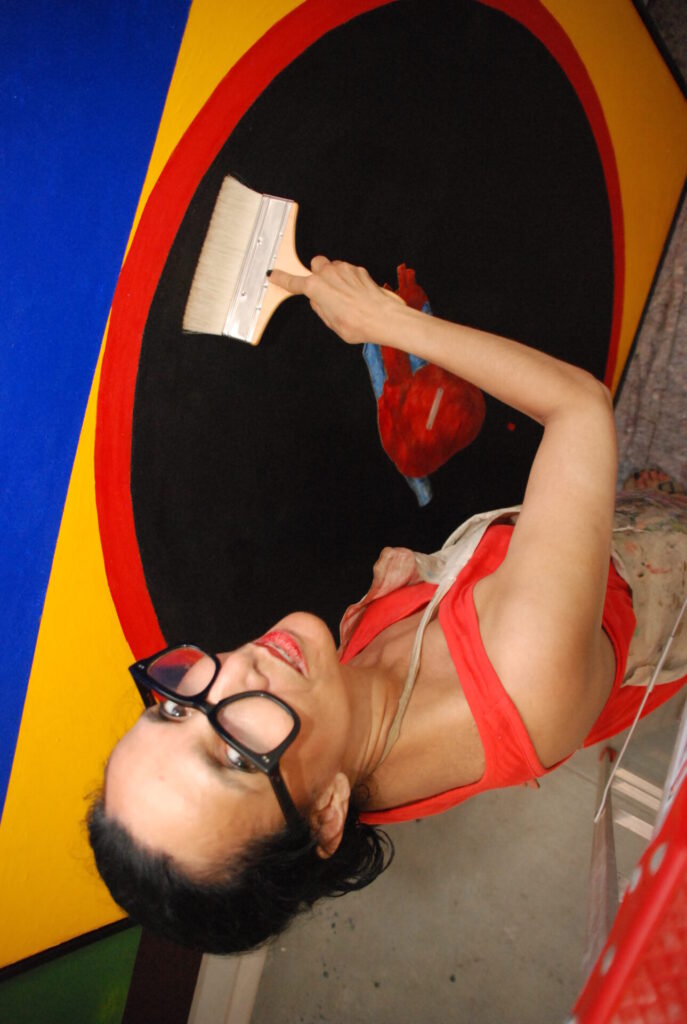

Beyond the academy, his training has led him to understand that daily life is an essential part of the artistic experience. For this reason, one of the rooms of the exhibition recreates a living room inspired by those intervened by Cárdenas in his Calentamientos happenings, in which he made conversation with, generated laughs from, and warmed up Dutch families.

This series of happenings was recorded and now forms part of the collection of videos of Cárdenas’ production company Warming up etc. etc. etc., whose logo, a flower/vagina is reproduced on wallpaper in the exhibition space.

Michel Cárdenas, a name that Miguel Ángel adopted in the Netherlands to avoid the catholic references of his name, read Bertrand Russell to find that it both echoed and confirmed his rejection of a suffocating and discriminating religion opposed to the ethics of freedom. The opinions of the mathematician-philosopher regarding religion and particularly Christianity, in particular his writings about the cruelty of dogmas rooted in society and the necessity of having a posture closer to reason and truth, became the artist’s bible.

For these reasons, Russell’s liberal views on sexuality and marriage seduced Cárdenas. Sexuality in its most eroticized and explicit sense is a fundamental theme in Cárdenas’ practice. Fluids, orgasms and wails can be understood as ”abject”, yet from Cárdenas’ perspective they will never be vulgar since the sexual act is sacred and beautiful.

Words like “fuck”, “cunt”, or “dick” form the parts of pieces such as Aren’t those parts of a beautiful act? through which Miguel Ángel tried to reveal the sublime aspect of sexual relations, both heterosexual and homosexual. His refreshing posture, both literal and conceptual, fitted perfectly within the queer aesthetic since it had the right dose of activism in a dominantly heterosexual society. Cárdenas understood warmth as the spirit of life and therefore created diverse pieces about warming up: Un cube se transforme en cercle par la chaleur de Cardena, Cárdena Rechauffe le soleil, Cardena Rechauffe la Bible and the photographic montage Cárdenas Rechauffe la bouche.

The piece Somos libres is a surreal and symbolic narrative of his migrations in search of a space that allowed him to emancipate his body and his existence.

His Tensages, made with PVC and other recycled elements, arose from his desire to work from the aesthetic of consumerism and, as thus, can be understood as pop art. First made in 1964, they are pioneer pieces that melt pop with sexual themes. Moreover, they can also be seen as the continuation of Cárdenas’ abstract painting practice.

Some of these works formed part of the seminal exhibition New Realists and Pop Art, which travelled from The Hague to Vienna and Brussels in 1964.

María Wills Londoño