Lo que el tiempo se llevó

The exhibition “Lo que el tiempo se llevó” reflects on memory and time through architecture and ornament, presented as ruins and structures that raise questions about the past. The exhibition includes works by three artists from different generations: Fernell Franco, Luis Ospina and Felipe Arturo. Using installations, photography and video, the exhibition tries to create relationships between these works. Through his work, Franco captured the extreme contrast in lighting and social contrast in the city of Cali during its rapid growth in the 1970s. Ospina, for her part, explored urban space through photography and film. Lastly, Arturo puts elements of architecture and landscape in tension against residues of colonial histories.

How does memory materialize itself ? Is it in an object, a place or a street? And what happens when this object disappears? How can our mind recall? Time carries away everything, feelings, thoughts, spaces… however they appear again, twisted by our mind and emotions. In this exhibition, architecture, ornament and furniture are presented as ruins and structures that propose reflections about that remote time that no longer exists.

The preservation notion that is evidenced by certain conservationist policies is useful in some cases for monuments, but what happens with these intimate places whose importance resides in personal histories? Daily life turns ephemeral as minutes go by and obliterate. The street that once was, the coffee shop down the corner that is now closed, the building where we grew up that vanished…We can feel alienated in our own environment, exiled in the same territory that suddenly or gradually changed. Building from emptiness, part of our stories lack solid foundations. That might be why memory generates vertigo.

Lo que el tiempo se llevó proposes an intimate dialogue between three artists whose works reflect on memory, understood from architectural space and the objects that inhabit it. Fernell Franco (1942-2006) and Luis Ospina (1949) belong to the generation that consolidated the city, Cali, as the protagonist of a creative wave in the 70s. Felipe Arturo’s (1979) sculptural practice generates a tension be-tween architectural elements and landscapes, and residues of colonial history. His revisions of cultural influences reveal that globalisation is not as recent at it is been understood in the lately.

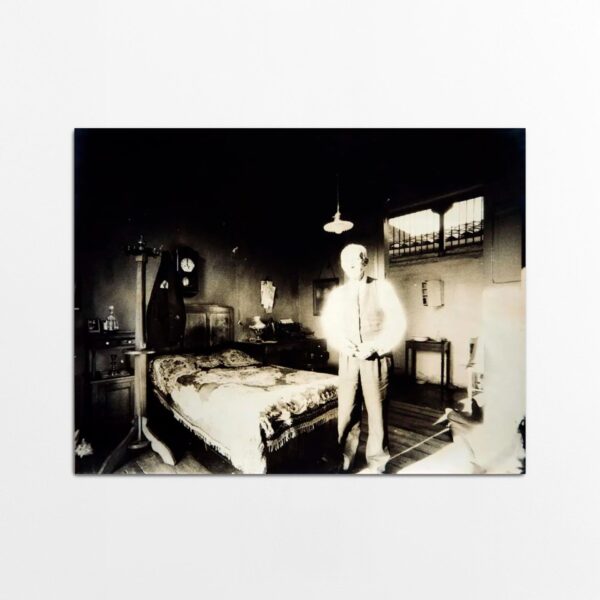

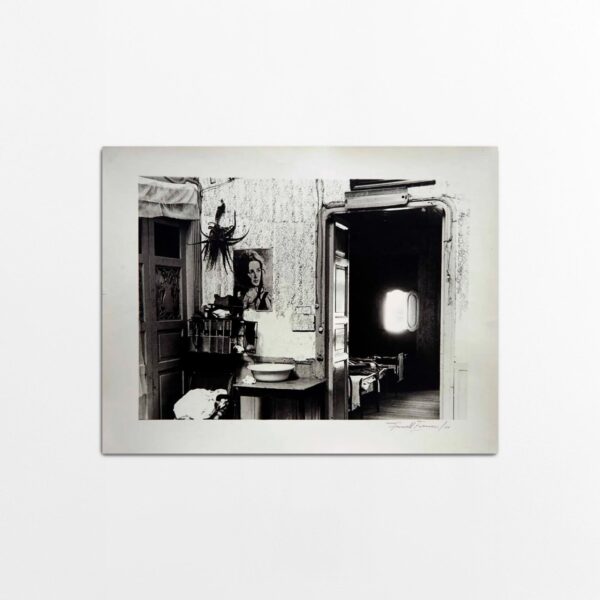

From languages as diverse as installation, photography and video, this exhibition proposes tensions among works of artists from different generations.The series Interiors, produced by Fernell Franco during the seventies are, more than testimonies about daily life of tenancies and homes of the city of Cali, sublimes paintings of light and shadow. Franco, one of the most important photographs of the country, captured in a unique manner the transcendence that the images’ extreme light contrast might have. In Maria Iovino’s interview, Franco affirms that contrast is not only a result of Cali’s meteorological conditions where midday lights are incandescent and blinding, but also as a means to express the social contrasts observed in this city of accelerated growth.

Franco explored Cali together with Oscar Muñoz, Eduardo Carvajal, Ever Astudillo and Luis Ospina for whose documentaries he did the still photography. From the beginning of the 70s, the urban, deeply investigated2, was one of the main themes of the Cali group. Fernell Franco registered disappearing spaces: beautiful buildings that would be destroyed to give place to concrete blocs. “The violence against architecture and heritage was similar to the one endured by men” declared the photograph mentioning this period of Cali’s history.

In these pieces, the artist captures recurring designs and ornamentations in villas (shared houses used as collective housing, inherited from the Andalusian-Arab culture) that show elements of neoclassic architecture. Moreover Franco’s practice involves a process that turns these photographs into unique pieces; he intervenes them with inks and colours as Pictorialism images or romantic studio photographs of the XIX century.

In dialogue with the Franco’s photographs, Felipe Arturo presents works that explores two fundamental themes of his practice: on one side, his interest in the his-tory of concrete, its role in the construction of a modern idea of architecture and its incomplete versions and, on the other side, the political, economical and cultural repercussions of the displacements undergone by some agricultural products and the consecutive meanings they acquire during their itinerary around the globe. Through the works presented in this exhibition, Arturo reveals moments of internal mechanisms between these two processes and formal encounters between the conceptual directions that move his practice. The body of work presented in this exhibition can be seen as a revision of previous pieces in which the artist reconsiders the preoccupations that characterized his practice.

Cosmo café announces a symbolic space based on the history of coffee. As text and object, this piece functions as the reconstruction of an imagined coffee place street sign. In this sense, it denotes the ubiquitous character of the coffee shop as space and cultural product, eroding the link between agricultural product and national identity. Furthermore, Cosmo Café makes reference to the project Cos-mo cocas (1973-1974) by Helio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida. The linguistic dis-placement of coca by coffee signals the parallel but antagonist histories of these plants: whereas cocaine became the most persecuted substance of recent history, caffeine established itself as the most accepted and consumed drug in the world.

Diarios de Azúcar registers the passing of the artist in different places through the daily consumption of coffee and sugar. Hung in a calendar like structure, this collection of sugar bags builds the narrative of a map and path trough the city, with disposable goods that local coffee places offer as sugar bags. Produced for the first time in Venice, these empty bags reveal two types of coffee places: the ones that still design their own products and the ones that use established brands. This minor detail highlights the resistances of some of those places to the total absorption of coffee culture by a massive transnational trade system. This work also signals the very old relation between Venice and coffee trade and the relation be-tween the first Western coffee places and the artistic, intellectual and political development of a city. Eventually the history of coffee and the history of art merge in Café Florian, where the idea of the Venice Biennial first originated. Finally, this piece positions the artist as a consumer signalling the historical processes in which he is himself meddled.

Through a process of experimentation with coffee as ink and a cup as a graphic instrument, the piece Los Viajes del café (Coffee travels) in which the cup is used as a circular stamp, creates, according to different types of overlays and reticules, the same patterns used as the geometrical bases of Islamic and Mediterranean design. Hung as screens, these coffee stained papers build a variable spatial sensation. The multi-referential history of these drawings recall the historical routes of coffee; the appropriation of this graphic patterns in Latin-America shares a common path with the history of coffee: from Ethiopia and Eritrea to Latin-America crossing the Arabic Peninsula, the Mediterranean costs and the Iberian Peninsula. These screens not only connect coffee’s historical and contemporary geographic routes, but also allow us to see differently the daily experience of this substance and its container.

Vin Mariani o Coca Cola retro is a basic reconstruction of Vin Mariani, a drink made of Bordeaux wine and coca leaves that became popular at the end of the XIX century and that constitute the direct antecedent of the Coca-Cola recipe. This work investigates the moment prior to the drug penalization, before certain substances were categorized as illegal, as wine or cocaine. The piece is constituted of three glass bottles, one with coca leaves, another one with wine and the third one with the mixture of both. Vin Mariani o Coca Cola retro is also an exercise of cultural syncretism as wine and coca were fundamental elements of antiques civilization such as the Roman and the Inca.

Mesas de polvo (Dust tables) is a series of table-buildings which overlap, trough their materials, two moments of the economical history of Latin America. These tables built in concrete, are intervened with coffee and white sugar powders or with objects such as modified coffee cups. Following the logic of vernacular concrete architecture, generally associated with the massive urbanization of Latin-American cities’, these tables incorporate antique designs produced with materials from the agricultural production.

Although we generally associate concrete with a modern period, coffee to a post-colonial one and sugar to the colonial period, these constructions try to link these textures within the same anachronistic object. Coffee and sugar patterns function as floor designs and game boards. These tables are also the consequence of multiple personal references, as chest boards, coffee places in Bogota’s centre, connections between Venetians and Colombian bars, Aldo Rossi’s drawings, San Marco’s mosaics or Caribbean floors. Variations of Incomplete Concrete Chairs is a system of permutations that allows to build a concatenations of concrete structures based on the skeleton of a chair. The project starts from the hybridization of the modern idea of geometric modulation and from the idea of progressive architecture found in some vernacular constructions. However, in this project the sense of incompleteness and progressiveness can be understood simultaneously from a structural point of view or from the perspective of individual development. Each of these chairs, at the same time furniture, building and construction, raises the question of the relation between the means of construction and individual development, questioning the mutual interferences between the psychological and the architectural realm.

The project also makes reference to the Sol Lewitt’ series of geometrical constructions of the sixties and seventies know as Variations of Incomplete Open Cubesin which he produced a series of representation, in two and three dimensions, of incomplete cubes.

In the video room, we present Adiós a Cali /¡Ah, diosa Kali! (Farewell to Cali): Luis Ospina’s poetic testimony about the architectural memory of his city. Cities are full of memories, scars, holes, and mutations. While these remain for some unnoticed amidst the daily frenzies, for others they imply sufferance or melancholy. Ospina nostalgically wanders about the Cali that no longer exist; a city that Eduardo Carranza described as “a dream crossed by a river”, a city with a very special provincial beauty.

Cali, in spite of been one of Colombia’s oldest cities, remained, until the beginning of the XXth century, constituted by five neighbourhoods built on former haciendas. In 1950 its population was only 240.000 inhabitants and today there are approximately 2.4 millions. In this fast period of growth, a monster called development accelerated the disappearance of this romantic time that Ospina once knew.

The video is divided in two chapters: in the first half it presents a visual experiment called Cali shot by shot and in the second part it reveals this process of loss by al-lowing the voice of artists from Cali to be heard. Without doubt, memories are ruins and this metaphor is the inspiration of this piece full of contrasts between spotless buildings and rubble and demolitions.

Ospina’s documentary practice has always been very close to art. To approach the city through video art allowed him to experiment and to include esthetical means such as stains that slowly swallows the image, colour saturations or recorded screens.

While looking at the video, we intimately sense what could the destruction of the soul feel, and we fear the lost of references with which our past in built. From this perspective, Ospina overlaps, as part of his visual proposal, home videos recorded by his father with fragments of Johnny Guitar’s movies. This video that dialogues intimately with Fernell Franco’s photographs (who is also one of the inter-viewed), can be seen as a memorial of corners, a tribute of architectural details even if it also presents the perspective of the wreckers, who, as one of them explains, demolish with “much love” for their work. Alienated, hopeless and stranger in his own land, Ospina decides to abandon Cali to move to Bogota. This piece is, as its title indicates, his farewell to Cali.

————————————————————————-

* Iovino Moscarella, María. “Fernell Franco, Otro documento” 2004 [Cali: Alianza Colombo Francesa, c2004. Available online: http://icaadocs.mfah.org/icaadocs/ELARCHIVO/RegistroCompleto/tabid/99/doc/860546/language/es-MX/Default.aspx

* “Cali, ciudad abierta, Arte y cinefilia en los setenta” Katia González Martínez. Ministerio de Cultura/Universidad de los Andes. 2013

*Descriptive texts of works by Felipe Arturo, made by the artist.

Bogotá

Carrera 23 # 76-74

Barrio San Felipe, Bogotá

Tel. +57 (60) 1 3226703

Lunes a Viernes

10:00 am a 05:30 pm