Óptica Mióptica · Posdata es arte

Vista general de la exposición Óptica mióptica y Posdata: es arte. Nicolás Consuegra y Pedro Terán.

Pedro Terán. Arte y los elementos, 1970 Impresión fotografía sobre cibachrome 88 x 60 cm.

Vista general de la exposición Óptica mióptica y Posdata: es arte. Santiago Rebolledo, Nicolás Consuegra y Pedro Terán.

Nicolás Consuegra La esquina flaca. Fibra de vidrio, yeso y madera contrachapada. 47.5 x 47.5 x 47.5 cm 2016.

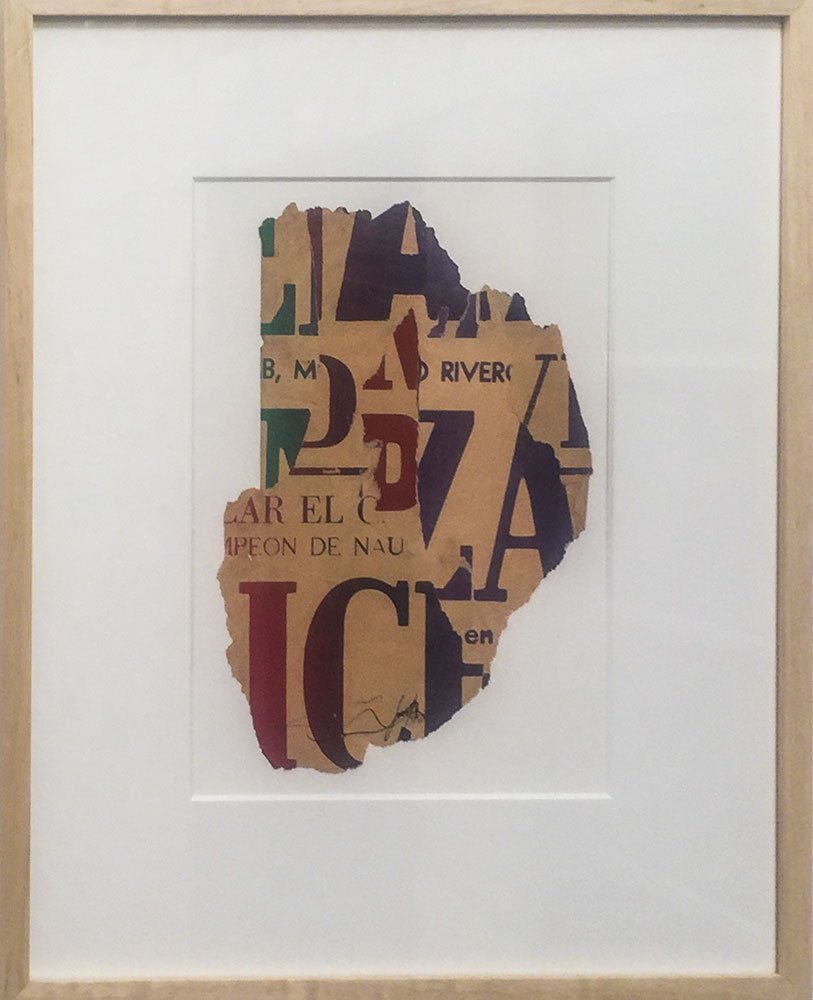

Santiago Rebolledo, Sin Título, circa. Xerografía. 52 x 42 cm. 1978.

Vista general de la exposición Óptica mióptica y Posdata: es arte. Santiago Rebolledo, Nicolás Consuegra y Pedro Terán.

Vista general de la exposición Óptica mióptica y Posdata: es arte. Nicolás Consuegra y Pedro Terán.

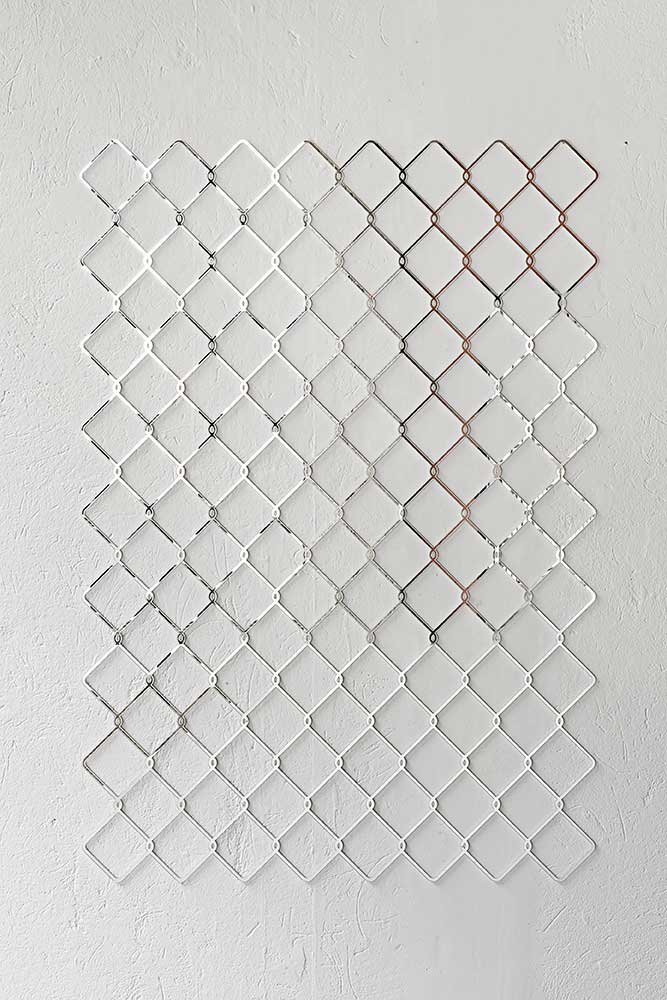

Nicolás Consuegra, Óptica mióptica. Cristal espejo. 180 x 90 cm. 2016.

Nicolás Consuegra, La muerte del padre. Madera y tela de algodón. 108 x 151 x 75.5 cm. 2016.

Vista general de la exposición Óptica mióptica y Posdata: es arte. Nicolás Consuegra y Pedro Terán.

Mirada sin nombre de Nicolás Consuegra, 2016. MDF. Dimensiones variables.

Mirada sin nombre de Nicolás Consuegra, 2016. MDF. Dimensiones variables.

Vista general de la exposición Óptica mióptica y Posdata: es arte. Nicolás Consuegra, Santiago Rebolledo y Pedro Terán.

Nicolás Consuegra. Planta libre, 2016. Impresión giclée sobre papel de conservación. 120 x 80 cm y Mirada sin nombre , 2016. MDF. Dimensiones variables.

Vista general de la exposición Posdata: es arte. Santiago Rebolledo y Pedro Terán.

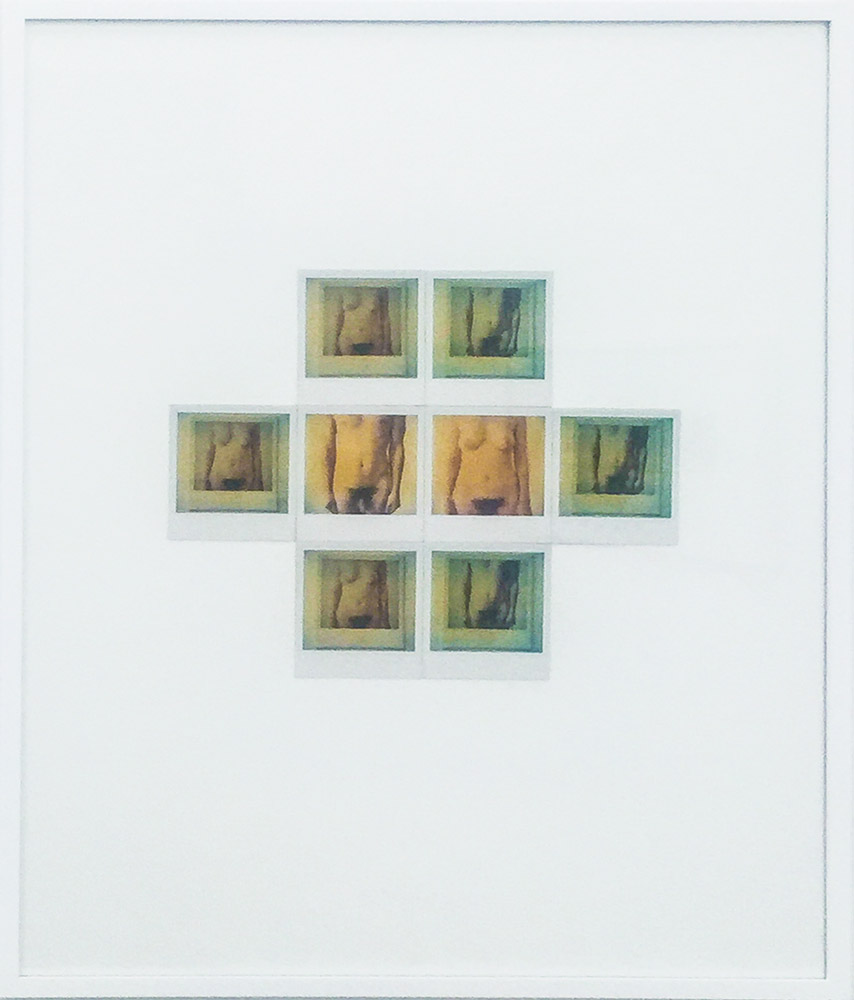

Pedro Terán. Polagramas Masculino y femenino, 1977. Polaroid SX70. Vintage. 76,5 x 57 cm.

Vista general de la exposición Posdata: es arte. Pedro Terán.

Vista general de la exposición Óptica mióptica y Posdata: es arte. Santiago Rebolledo y Nicolás Consuegra.

Nicolás Consuegra· Óptica mióptica

Como lo ha manifestado en proyectos anteriores, Nicolás Consuegra emplea elementos de uso cotidiano para abordar temas que le interesan sobre el espacio, las relaciones entre lo funcional y lo no-funcional así como la percepción visual; temas que a su vez le permiten responder a inquietudes que tiene en torno al trabajo (como actividad simbólica y material), y valores socioculturales como la unidad y la colectividad.

En Planta libre, Nicolás recuerda el paradigma arquitectónico del mismo nombre en una situación donde el modelo y la mano (que le da forma) se entrelazan para cuestionar la dimensión simbólica de cada uno. Los dedos-pilotes, sugieren cierta estabilidad constructiva, sin embargo, la disposición de los planos nos hace reflxionar sobre el movimiento orgánico de los dedos. Para Nicolás, esta situación intenta señalar el orden y la disciplina que ha ejercido el modelo (moderno) en los espacios geográficos en los que que se ha implementado y cómo son estos últimos, han acogido o resistido a dicho modelo.

Un espejo con la figura de una malla entrelazada —y qué da el título a esta misma exposición, Óptica mióptica—, nos indica la tensión entre nuestra especular y una pieza que también nos sugiere la posibilidad de mirar a través.

En El principio del trabajo, se observa una mesa de comedor que se prolonga, para proyectarse a manera de palíndromo o de antípoda de sí misma. ¿Son los individuos/fuerza de trabajo (las sillas) quienes soportan el sistema/capital (la mesa) o es el sistema quien soporta a los individuos?. Cerca de esta pieza hay otra que también está compuesta de elementos similares pero ligada a referentes distintos (la “metáfora paterna”, según Lacan, entre otras ): en La muerte del padre, las sillas crecen a manera de rizomas de una mesa que indica una posición cesante.

En Mirada sin nombre, Nicolás plantea una serie relaciones en torno al acto de observar y ser observado, así como de la posibilidad del desplazamiento espacial de la mirada. Por la disposición espacial de estas piezas, Nicolás también refrlexiona en torno a la formalidad o informalidad del negocio inscrito en un ámbito artístico.

La presencia de dos búhos que descansan sobre su palo y titulados Naturaleza muerta, traen a la vida la marca de Colcultura —entidad creada en 1968 y que dejó de existir para dar paso al actual Ministerio de Cultura en 1997. Las dos versiones, diseñadas por Marta Granados (figura elongada, ca 1968) y Carlos Duque (figura triangular, 1983) respectivamente, señalan la tendencia de ciertas instituciones por emplear esta ave como parte de su identidad visual. El búho, que también se asocia con la figura de una lechuza (y más estrictamente un mochuelo), tiene un antecedente en occidente de ser el ave que acompaña a Atenea, diosa de la sabiduría y las artes, entre otras. Pero su uso no ha sido constante desde la antigüedad. Hegel por ejemplo, la trae de nuevo a la luz, citando la lechuza en el prefacio de sus Fundamentos de la filosofía del derecho (1820), y Ortega y Gasset la utiliza como sello de la emblemática Revista de Occidente (1923). En nuestro contexto, este búho —o mejor dicho— estos búhos, marcaron una época de la cultura en Colombia y fueron una suerte de figuras tanto vigilantes y enigmáticas como perdurables; aún cuando Colcultura dejara de existir.

En La esquina flaca, Nicolás señala el punto donde los planos de las paredes y el suelo se juntan, pero al hacerlo, se funden las unas con el otro. Esta es una pieza que recuerda un trabajo previo suyo, en el que dio una presencia primordial a un fondo sinfín —dispositivo utilizado en el campo de la fotografía y cuya condición es no ser visible—.

———————-

Posdata: es arte

El término Bellas Artes se consolidó en el Siglo XVIII para referirse a las principales artes y buen uso de la técnica. Incluyó disciplinas como la escultura, la danza, la pintura, la poesía, la música y la arquitectura y buscaba dar unos ciertos parámetros para definir el buen gusto.

Aunque la sociedad es terca en entenderlo, lo artístico desde hace más de un siglo, ya no es una cuestión de “buen gusto”. El arte como ornamento pasa a segundo plano y se convierte más en un proceso de pensamiento. Lo que en sus inicios fue un camino evolutivo hacia la belleza y la ilusión, se vuelve una caída al vacío, algo indefinible, inabarcable, la obra de arte se desmaterializa, se vuelve filosofía de pensamiento y se aleja de lo comprensible.

¿Qué es arte y qué no lo es? La pregunta surge como punto de partida del proceso artístico desde inicios del siglo XX, en donde artistas como Duchamp respondieron con un orinal o Piero Manzoni con tarro de mierda. La pregunta puede resultar tautológica, puesto que arte es lo que el artista decida que lo es.

Bajo estas premisas se presenta dentro del programa Visionarios el trabajo de los artistas Pedro Terán y Santiago Rebolledo.

Pedro Terán (1943, Barcelona, Venezuela)

Pedro Terán, es un artista cuyo trabajo redefine los parámetros del arte venezolano en la década de los setenta al introducir prácticas conceptuales que buscaban plantear la pregunta de qué tan posible es que la vida misma sea arte. A la par que artistas en otras latitudes, involucrar la cotidianidad desde sus objetos y actividades fue fundamental para Terán quien salió a la calle a realizar sus obras, buscando que el arte estuviera en el deambular. Así puso sellos con la palabra arte en los cuerpos de transeúntes y en el espacio público, igualmente dispone huellas en los andenes para introducir nuevas maneras de caminar.

Es un honor para el Instituto de Visión recibir a este visionario 35 años después de su participación en uno de los eventos más trascendentales para la redefinición de las artes visuales de Colombia, como fue el Coloquio de Arte no Objetual realizado en Medellín en 1981, con la coordinación de Alberto Sierra y la Dirección artística de Juan Acha. Allí Terán presentó el performance “Nubes para Colombia” en el cual tomando el mito de “El Dorado” hizo una versión de ritual/ofrenda con su cuerpo pintado de oro.

Santiago Rebolledo (1951, Bogotá, Colombia)

El grupo Suma se engloba dentro de un vasto campo de colectivos que participan en el circuito artístico de México a finales de los setenta, años de los cuales hacen parte artistas jóvenes deseosos de incorporar en su obra la crítica a una sociedad llena de tensiones sociales y marcada por la violencia del estado. El evento crítico que catapultó una cascada de trabajos artísticos y que fue dramáticamente ilustrado fue el 2 de octubre de 1968, cuando la ciudad fue sede de los Juegos Olímpicos, durante los cuales hubo una importante manifestación estudiantil en la Plaza de las Tres Culturas que fue dispersada violentamente por la policía y en donde hubo cientos de muertos.

Los artistas de Suma, dentro de los cuales estaba Santiago Rebolledo, trabajaron mayoritariamente bajo la sombrilla del colectivo que firmaba con sus siglas y logo (una águila mexicana) para mantener un anonimato que los protegía de las arbitrariedades del estado ante sus actos de protesta. Este grupo buscó redefinir el arte acercándose de una manera diferente al público, y construyendo su práctica sin depender de las instituciones. Incorporaron en su obra el reciclaje, usando carteles arrancados de paredes y otra serie de desechos.

Aunque su trabajo fue primordialmente realizado en colectivo, es importante destacar al igual que sucedió con el Taller 4 Rojo en Colombia que hay una serie de enfoques personales, que aparecen aquí y allá. Santiago Rebolledo utiliza el vocabulario urbano – los objetos encontrados, recortes de revistas, sobres, estampillas, afiches de políticos- para hacer collages y plissages que combinan y superponen recortes y que hacen uso de manera pionera de la mimeografía y fotocopia.

María Wills Londoño

As manifested in previous projects, Nicolás Consuegra uses everyday items to address issues related to space, to relationships between function and non-function, to visual perception, to reflections about labour (as a symbolic and material activity), and to

the unit and the collectivity.

In Free plant, Nicolás recalls the architectural paradigm of the same name; the model and the hand that models it are intertwined, reversing each other’s symbolic dimension. Fingers as piles suggest the planes’ stability, however, it is the latter that restrict their organic movement.

A mirror shaped as a grate frame -piece that gave its title to the exhibition- Myoptic Optics, suggests the difficulty of seeing through or forward due to the obstinacy of staring at oneself.

In The principle of work, a dining table extends itself into its own projection, as a palindrome or an antipode of itself. What supports what? Are chairs (individuals) those who hold up the table (a system)? Is the table holding the chairs?

In another work, Nicolas uses similar elements however linked to different references. In The Death of the Father, chairs are growing as rhizomes of a table in a way that indicates a posture of unemployment.

Eyewear models presented in Unnamed Glance expose a multiple dimension that seeks to alter our insistence on a dichotomous and polarized gaze-perhaps as a consequence of a bodily symmetry that we do not question.

The presence of some owls in Still Life, symbol used previously as part of the image of Colcultura - entity that disappeared to give way to the current Ministry of Culture- and designed at that time by Marta Granados and Carlos Duque, emphasizes the interest of certain institutions to employ a bird as symbol for a cultural agency. Furthermore, the owl has a special connotation in the West as it is the bird that accompanies Minerva, goddess of wisdom, in Ancient Greek mythology. This owl-or moreover, these owls- marked an era of the culture in Colombia; they were a kind of vigilant and enigmatic figures that linger in cultural productions and continue to circulate in our memory, long after Colcultura ceased to exist.

Finally, in Thin Corner, Nicolas presents this specific point where the planes of the walls and that of the floor meet, and by doing so, merge in each other. This piece recalls an earlier work related to endless corners, commonly used in photography and whose condition is to not appear.

In reviewing constructive and symbolic elements, Nicolas seeks to reflect on the relationships between individual and collective work, between variations and deconstructions of the same object, its initial utility and our persistence to impose our understanding upon what is presented before our eyes.

------------------------------------------------------

Postscript: this is Art

The term Fine Arts was consolidated in the XVIII century to refer to the main arts and good use of technique. It included disciplines such as sculpture, dance, painting, poetry, music and architecture and sought to provide certain parameters defining good taste.

Although society shows stubbornness in understanding and accepting it: for more than a century, art ceased being matter of "good taste". Art as ornament recedes into the background to leave its space to a process of thought. What was at the beginning an evolutionary path towards beauty and illusion becomes a fall into the void, something indefinable, incomprehensible; the artwork is dematerialized; it becomes a philosophy of thought and walks away from the understandable.

What is Art and what is not? The question arose as the starting point of artistic processes since the beginning of the XX century when artists like Duchamp responded with a urinal or Piero Manzoni with a jar of shit. However, this question may result tautological since art is what the artist decides it to be.

Under these assumptions, IV presents as part its Visionaries program, the works of Pedro Terán and Santiago Rebolledo.

Pedro Terán (1943, Barcelona, Venezuela)

Pedro Terán is an artist whose work redefined the parameters of Venezuelan art in the seventies by introducing conceptual practices that raised the question of the possibility that life itself could be art. Along with artists in other latitudes, involving everyday life, its objects and activities was fundamental to Terán who went out to the streets to produce his works; his art was all about wandering. He put stamps with the word art on passersby, and set up new tracks to establish new ways of walking.

He studied at the School of Fine Arts in Caracas, the School of Fine Arts in Rome and the London Film School. Leaving his country allowed him to deepen his proposal: art was in the body itself, in the experience and in the wandering. The object was a simple consequence, never the central mission of his work.

Simultaneously to movements such as Fluxus, which was active in the sixties and seventies, his best known works seek to avoid art as merchandise, and operate from a different dialectic where its definition is precisely indefinable. In several of his most important works, his body becomes an extension of the landscape or space. In works such as "Body Exposure" (1975) or "Fabric" (1977) his body, usually naked, is fragmented to camouflage itself or inserted into the reality in a almost abstract manner.

As mentioned in Gabriela Rangel’s text for El Museo del Barrio’s catalogue "Arte ≠ Vida: Actions by Artists of the Americas 1960-2000", using gestures of extreme masculinity, Terán unfolds his body to feminize it and show his subjectivity. In this sense, Terán makes a theoretical demarcation between performances -events that establish an intimate connection between the viewer, the body and the subjectivity that arises as time is ritualised- and, on the other side, actions directed towards public spaces where what happens is not inscribed in a ritual.

On the other hand, it is impossible to deny the abstract tradition when one is the heir of Venezuelan kinetic art. Terán was close to Otero and his interest in this optical abstraction is revealed in the polagramas; compositions made with multiple polaroids as part of a continuum or as fragments of an almost always abstract structure. The pieces seem to want to give movement to the photographs.

It is an honour for Instituto de Vision to welcome this visionary 35 years after his participation in one of the most important event for the redefinition of visual arts in Colombia -the Colloquium of Non-Objectual Art held in Medellin in 1981- coordinated by Alberto Sierra and with Juan Acha as artistic director. There Terán presented the performance "Clouds for Colombia" in which, taking the myth of "El Dorado" as starting point, he presented an offering with his body painted in gold.

Santiago Rebolledo (1951, Bogotá, Colombia)

Suma group is part of a large group of collectives that participated in Mexico’s artistic scene at the end of the seventies; years in which young artists were eager to incorporate in their work the criticism towards a society full of social tensions and marked by state violence. The critical event that catalysed a great number of artistic works was the October 2nd 1968 massacre during a demonstration in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas where students were violently dispersed by the police causing hundreds of deaths.

Art in public space, in Mexico as elsewhere, is often linked to state commissions. In the first half of the XX century, the great Mexican muralists (Rivera, Siqueiros and Orozco), called for the decoration of public buildings, created a particular and visually abundant expression, which orchestrated the construction of the country’s cultural identity. In contrast, Suma artists, also occupy the walls of the city, however without being invited. Their interventions combined signs, words and abstraction, and incorporate elements or techniques of urban popular culture that are often ephemeral. An ambiguous relationship of extreme instability is then created between supports, which are often walls, or in some cases simple sheets, and fragments of newspapers or posters. Suma then developed a new, more global and multicultural visual identity that exalts in an ironic way, objects of mass culture.

Suma artists, among which was Santiago Rebolledo, worked mostly under the umbrella of the group who signed with its initials and logo (a Mexican eagle) to maintain an anonymity that would protect them from the arbitrariness of the state in front of their protest acts. This group sought to redefine art by approaching the public in a different way, building their work without relying on institutions. Using posters torn from walls and other waste from mass culture, they incorporated recycling in their work.

Although Rebolledo’s work was done mainly collectively, it is important to highlight, as it is the case in Taller 4 Rojo in Colombia, that personal approaches appear here and there. Santiago Rebolledo uses urban vocabulary - found objects, clippings from magazines, envelopes, stamps and political posters- to make collages and plissages that combine and overlap clippings; moreover they are pioneer in the use of

mimeograph and photocopy.

Rebolledo took engraving courses with Humberto Giangrandi at the University of the Andes and in 1974, he joined the Taller 4 Rojo and Jorge Tadeo Lozano University of Fine Arts. In 1975 he emigrated to Mexico to study mural painting and there he developed his artistic career.

Suma, during its seven years of existence from 1976 to 1982, was composed of twenty artists: Oscar Aguilar Olea, Jose Barbosa, Paloma Diaz Abreu, René Freire, Oliverio Hinojosa, Armandina Lozano, Gabriel Macotela, Ernesto Molina, Alfonso Moraza, César Núñez, Hirman Ramirez, Armando Ramos, Mario Rangel Faz, Santiago Rebolledo, Jesus Reyes Cordero, Ricardo Rocha, Jaime Rodriguez, Arturo Rosales, Patricia Salas, Alma Valtierra, Luis Vidal, Guadalupe Sobarzo.

María Wills Londoño